1. Searching for gold inside HTML files¶

It used to take days for financial news to spread via radio, newspapers, and word of mouth. Now, in the age of the internet, it takes seconds. Did you know news articles are automatically being generated from figures and earnings call streams? Hedge funds and independent traders are using data science to process this wealth of information in the quest for profit.

In this notebook, we will generate investing insight by applying sentiment analysis on financial news headlines from FINVIZ.com. Using this natural language processing technique, we can understand the emotion behind the headlines and predict whether the market feels good or bad about a stock. It would then be possible to make educated guesses on how certain stocks will perform and trade accordingly. (And hopefully, make money!)

Why headlines? And why from FINVIZ?

- Headlines, which have similar length, are easier to parse and group than full articles, which vary in length.

- FINVIZ has a list of trusted websites, and headlines from these sites tend to be more consistent in their jargon than those from independent bloggers. Consistent textual patterns will improve the sentiment analysis.

As web scraping requires data science ethics (sending a lot of traffic to a FINVIZ's servers isn't very nice), the HTML files for Facebook and Tesla at various points in time have been downloaded. Let's import these files into memory.

Disclaimer: Investing in the stock market involves risk and can lead to monetary loss. The content in this notebook is not to be taken as financial advice.

# Import libraries

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

import os

html_tables = {}

# For every table in the datasets folder...

for table_name in os.listdir('datasets'):

#this is the path to the file. Don't touch!

table_path = f'datasets/{table_name}'

# Open as a python file in read-only mode

table_file = open(table_path, 'r')

# Read the contents of the file into 'html'

html = BeautifulSoup(table_file)

# Find 'news-table' in the Soup and load it into 'html_table'

html_table = html.find(id='news-table')

# Add the table to our dictionary

html_tables[table_name] = html_table

%%nose

import bs4

def test_load_html():

assert type(html) == bs4.BeautifulSoup, \

'You should load the BeautifulSoup objects in variable named html.'

def test_load_html_table():

assert type(html_table) == bs4.element.Tag, \

'You should load the news-table tags in the variable named html_table.'

def test_load_html_tables():

assert len(html_tables) == 5, \

'You should load all five tables in the html tables dictionary.'

def test_html_tables_has_data():

assert type(html_tables['tsla_26nov.html']) == bs4.element.Tag, \

'You should load the news-table elements into the html_tables dictionary.'

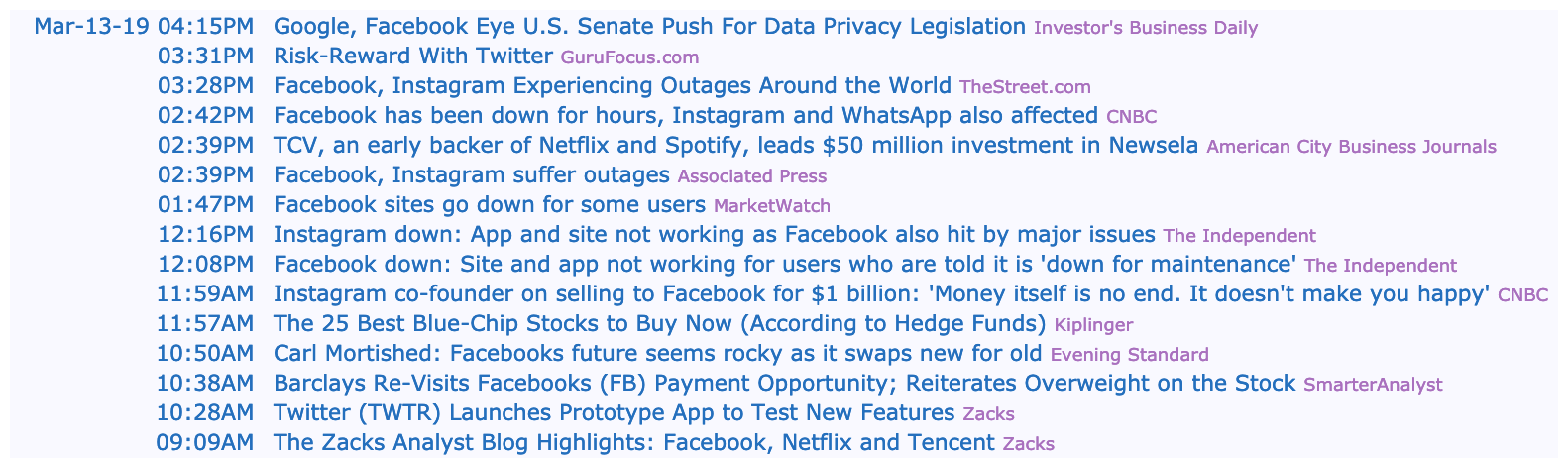

2. What is inside those files anyway?¶

We've grabbed the table that contains the headlines from each stock's HTML file, but before we start parsing those tables further, we need to understand how the data in that table is structured. We have a few options for this:

- Open the HTML file with a text editor (preferably one with syntax highlighting, like Sublime Text) and explore it there

- Use your browser's webdev toolkit to explore the HTML

- Explore the headlines table here in this notebook!

Let's do the third option.

# Read one single day of headlines

tsla = html_tables['tsla_22sep.html']

# Get all the table rows <tr> in the file into 'tesla_tr'

tsla_tr = tsla.findAll('tr')

# For each row...

for i, table_row in enumerate(tsla_tr):

# Read the text of the element 'a' into 'link_text'

link_text = table_row.a.get_text()

# Read the text of the element <td> into 'data_text'

data_text = table_row.td.get_text()

# Print the count

print(f'File number {i+1}:')

# Print the contents of 'link_text' and 'data_text'

print(link_text)

print(data_text)

# The following exits the loop after four rows to prevent spamming the notebook, do not touch

if i == 3:

break

%%nose

def test_link_ok():

assert link_text == "Tesla's People Problem and the Inscrutable Musk: 2 Things That Make You Go Hmmm", \

"Iterate through table_row and load link_text exactly 3 times."

def test_data_ok():

assert data_text == '05:30PM\xa0\xa0', \

"Iterate through table_row and load data_text exactly 3 times."

3. Extra, extra! Extract the news headlines¶

As we saw above, the interesting data inside each table row (<tr>) is in the text inside the <td> and <a> tags. Let's now actually parse the data for all tables in a comfortable data structure.

# Hold the parsed news into a list

parsed_news = []

# Iterate through the news

for file_name, news_table in html_tables.items():

# Iterate through all tr tags in 'news_table'

for x in news_table.findAll('tr'):

# Read the text from the tr tag into text

text = x.get_text()

# Split the text in the td tag into a list

date_scrape = x.td.text.split()

# If the length of 'date_scrape' is 1, load 'time' with the only element

# If not, load 'date' with the 1st element and 'time' with the second

if len(date_scrape) == 1:

time = date_scrape[0]

else:

date = date_scrape[0]

time = date_scrape[1]

# Extract the ticker from the file name, get the string up to the 1st '_'

ticker = file_name.split("_")[0]

# Append ticker, date, time and headline as a list to the 'parsed_news' list

parsed_news.append([ticker, date, time, x.a.text])

%%nose

import pandas as pd

def test_date():

assert pd.DataFrame(parsed_news)[1].sort_values().unique()[4] == 'Jan-01-19', \

'All dates should be loaded in the 2nd column, with format like in "Jan-01-19"'

def test_time():

assert pd.DataFrame(parsed_news)[2].sort_values().unique()[4] == '01:06PM', \

'All dates should be loaded in the 2nd column, with format like in "01:06PM"'

def test_ticker():

assert list(pd.DataFrame(parsed_news)[0].sort_values().unique()) == ['fb', 'tsla'], \

'The tickers loaded in parsed_news should be "tsla" and "fb". They should be the 1st column.'

def test_num_headlines():

assert len(parsed_news) == 500, \

'The parsed_news list of lists should contain exactly 500 elements.'

def test_len_data():

assert len(parsed_news[9]) == 4, \

'You should have exactly 4 elements inside each sub-list.'

4. Make NLTK think like a financial journalist¶

Sentiment analysis is very sensitive to context. As an example, saying "This is so addictive!" often means something positive if the context is a video game you are enjoying with your friends, but it very often means something negative when we are talking about opioids. Remember that the reason we chose headlines is so we can try to extract sentiment from financial journalists, who like most professionals, have their own lingo. Let's now make NLTK think like a financial journalist by adding some new words and sentiment values to our lexicon.

# NLTK VADER for sentiment analysis

from nltk.sentiment.vader import SentimentIntensityAnalyzer

# New words and values

new_words = {

'crushes': 10,

'beats': 5,

'misses': -5,

'trouble': -10,

'falls': -100,

}

# Instantiate the sentiment intensity analyzer with the existing lexicon

vader = SentimentIntensityAnalyzer()

# Update the lexicon

vader.lexicon.update(new_words)

%%nose

import nltk

def test_vader():

assert type(vader) == nltk.sentiment.vader.SentimentIntensityAnalyzer, \

'The vader object should be a SentimentIntensityAnalyzer instance.'

def test_lexicon_len():

assert len(vader.lexicon) >= 7504, "The lexicon should have been enriched with at least 5 words."

5. BREAKING NEWS: NLTK Crushes Sentiment Estimates¶

Now that we have the data and the algorithm loaded, we will get to the core of the matter: programmatically predicting sentiment out of news headlines! Luckily for us, VADER is very high level so, in this case, we will not adjust the model further* other than the lexicon additions from before.

*VADER "out-of-the-box" with some extra lexicon would likely translate into heavy losses with real money. A real sentiment analysis tool with chances of being profitable will require a very extensive and dedicated to finance news lexicon. Furthermore, it might also not be enough using a pre-packaged model like VADER.

import pandas as pd

# Use these column names

columns = ['ticker', 'date', 'time', 'headline']

# Convert the list of lists into a DataFrame

scored_news = pd.DataFrame(parsed_news, columns=columns)

# Iterate through the headlines and get the polarity scores

scores = [vader.polarity_scores(headline) for headline in scored_news.headline]

# Convert the list of dicts into a DataFrame

scores_df = pd.DataFrame(scores)

scored_news.columns = columns

# Join the DataFrames

scored_news = scored_news.join(scores_df)

# Convert the date column from string to a date

scored_news['date'] = pd.to_datetime(scored_news.date).dt.date

%%nose

import datetime

def test_scored_news_columns():

assert list(scored_news.columns[:4]) == ['ticker', 'date', 'time', 'headline'], \

"Don't forget to add the column names to the DataFrame. They first 4 should be ['ticker', 'date', 'time', 'headline']. The rest are set automatically."

def test_shape_scored_news():

assert scored_news.shape == (500, 8), \

'The DataFrame scored_news should have exactly 500 rows and 8 columns.'

def test_shape_scores_df():

assert scores_df.shape == (500, 4), \

'The DataFrame scores_df should have exactly 500 rows and 4 columns.'

def test_first_date():

assert scored_news.date.min() == datetime.date(2018, 9, 18), "Convert the column date to a *date* (not a datetime)."

def test_min_score():

assert scored_news[["neg", "pos", "neu"]].min().min() >= 0 , "neg, pos and neu cannot be smaller than 0."

def test_max_score():

assert scored_news[["neg", "pos", "neu"]].max().max() <= 1, "neg, pos and neu cannot be bigger than 1."

def test_min_comp():

assert scored_news["compound"].min() >= -1, "The compounded score cannot be bigger than -1."

6. Plot all the sentiment in subplots¶

Now that we have the scores, let's start plotting the results. We will start by plotting the time series for the stocks we have.

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

plt.style.use("fivethirtyeight")

%matplotlib inline

# Group by date and ticker columns from scored_news and calculate the mean

mean_c = scored_news.groupby(['date', 'ticker']).mean()

# Unstack the column ticker

mean_c = mean_c.unstack('ticker')

# Get the cross-section of compound in the 'columns' axis

mean_c = mean_c.xs("compound", axis="columns")

# Plot a bar chart with pandas

mean_c.plot.bar(figsize = (10, 6));

%%nose

def test_mean_shape():

assert mean_c.shape == (23, 2), '"mean_c" should have exactly 23 rows and 2 columns.'

def test_ticker():

assert mean_c.columns.name == 'ticker', 'you should group by and unstack the column ticker.'

def test_cols():

assert list(mean_c.columns) == ['fb', 'tsla'], 'Columns should be "fb" and "tsla".'

7. Weekends and duplicates¶

What happened to Tesla on November 22nd? Since we happen to have the headlines inside our DataFrame, a quick peek reveals that there are a few problems with that particular day:

- There are only 5 headlines for that day.

- Two headlines are verbatim the same as another but from another news outlet.

Let's clean up the dataset a bit, but not too much! While some headlines are the same news piece from different sources, the fact that they are written differently could provide different perspectives on the same story. Plus, when one piece of news is more important, it tends to get more headlines from multiple sources. What we want to get rid of is verbatim copied headlines, as these are very likely coming from the same journalist and are just being "forwarded" around, so to speak.

# Count the number of headlines in scored_news (store as integer)

num_news_before = scored_news.headline.count()

# Drop duplicates based on ticker and headline

scored_news_clean = scored_news.drop_duplicates(subset=['headline', 'ticker'])

# Count number of headlines after dropping duplicates (store as integer)

num_news_after = scored_news_clean.headline.count()

# Print before and after numbers to get an idea of how we did

f"Before we had {num_news_before} headlines, now we have {num_news_after}"

%%nose

def test_df_shape():

assert scored_news_clean.shape == (476, 8), '"scored_news_clean" should have 476 rows and 8 columns.'

def test_df_cols():

l = list(scored_news.columns)

l.sort()

assert l == ['compound', 'date', 'headline', 'neg', 'neu', 'pos', 'ticker', 'time'], \

'"scored_news_clean" should still have the same column names as scored_news.'

def test_scored_news_counts():

assert (num_news_before, num_news_after) == (500, 476), \

'"num_news_before" should be 500 and "num_news_after" should be 476.'

8. Sentiment on one single trading day and stock¶

Just to understand the possibilities of this dataset and get a better feel of the data, let's focus on one trading day and one single stock. We will make an informative plot where we will see the smallest grain possible: headline and subscores.

# Set the index to ticker and date

single_day = scored_news_clean.set_index(['ticker', 'date'])

# Cross-section the fb row

single_day = single_day.xs('fb')

# Select the 3rd of January of 2019

single_day = single_day.loc['2019-01-03']

# Convert the datetime string to just the time

single_day['time'] = pd.to_datetime(single_day['time']).dt.time

# Set the index to time and sort by it

single_day = single_day.set_index('time')

# Sort it

single_day = single_day.sort_index()

%%nose

import datetime

def test_shape():

assert single_day.shape == (19, 5), 'single_day should have 19 rows and 5 columns'

def test_cols():

assert list(single_day.columns) == ['headline', 'compound', 'neg', 'neu', 'pos'], \

'single_day column names should be "headline", "compound", "neg", "neu" and "pos"'

def test_index_type():

assert type(single_day.index[1]) == datetime.time, 'The index should be of type "datetime.type"'

def test_index_val():

assert single_day.index[1] == datetime.time(8, 4), 'The 2nd index value should be exactly "08:04:00"'

9. Visualize the single day¶

We will make a plot to visualize the positive, negative and neutral scores for a single day of trading and a single stock. This is just one of the many ways to visualize this dataset.

TITLE = "Negative, neutral, and positive sentiment for FB on 2019-01-03"

COLORS = ["red","orange", "green"]

# Drop the columns that aren't useful for the plot

plot_day = single_day.drop(['compound', 'headline'], 1)

# Change the column names to 'negative', 'positive', and 'neutral'

plot_day.columns = ['negative', 'neutral', 'positive']

# Plot a stacked bar chart

plot_day.plot.bar(stacked = True, figsize=(10, 6), title = TITLE, color = COLORS).legend(bbox_to_anchor=(1.2, 0.5))

plt.ylabel("scores");

%%nose

import datetime

def test_shape():

assert plot_day.shape == (19, 3), 'plot_day should have 19 rows and 3 columns.'

def test_cols():

assert list(plot_day.columns) == ['negative', 'neutral', 'positive'], \

'plot_day column names should be "negative", "neutral" and "positive".'

def test_index_type():

assert plot_day.index.name == 'time', 'The index should be named "time".'